‘I’ve matched with this girl on Tinder, should I buy her a pony?’ On the economics of romantic gestures.

‘The very essence of romance is uncertainty.’ Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Ernest

It is a common misconception that economists don’t have feelings. We do, just like normal people. But we do tend to struggle a bit when it comes to expressing those feelings, due to our natural pragmatism that has been enhanced by years of training. If you tell someone you really like that they are second best, an economist will understand this is a massive compliment: this person is the best you could ever hope to find in a real, imperfect world. However, someone less trained in distinguishing between feasible and non-feasible solutions may find this rather odd and offensive. Why wouldn’t you just tell them they are first best, or simply perfect?

For an economist, the answer is straightforward: because they’re not. They steal your fries, they snore, they are always late, they still haven’t quit smoking. Which doesn’t matter to you, because no one is perfect (not even you yourself), so they are still the very best. Just not first best. Now you could try and explain this to them, but judging from my experience, it’s usually better to remember that telling someone they are perfect is cheap talk anyway and choose harmony over accuracy.

However, there are situations where an economic background is really helpful, especially the ability to distinguish between cheap talk and meaningful signals. One of these situations is the initial dating phase with a potential significant other – the first couple of weeks after meeting someone, when you’re trying to find out whether you’re a good fit for each other. This phase is usually characterised by a profound feeling of uncertainty. You don’t know the other person yet, you don’t quite trust them, you don’t know what they’re feeling and how committed they are. You wouldn’t check your phone every other minute to see if there’s a message if you were certain there will be one at some point. You wouldn’t annoy your friends with endless discussions on how to interpret the three-word text message you got if you were certain it means what it says. You’re always hoping for the best and expecting the worst. It’s like a roller coaster ride (yeah, I know it’s cliché, but the analogy just works so well here). While there’s a reason most people like roller coasters, there’s also a reason why a roller coaster ride is usually quite short. As exciting as it can be, it’s also stressful, and it’s nothing you want to be doing for too long.

So how do you get off the roller coaster? You reduce uncertainty. Which is easier said than done. You can tell the other person you like them, but this will only get you so far. They don’t know you, so how should they know they can trust what you’re saying? What you need to convince them you really care is something that costs you. A costly signal, as an economist would say. In our context here, that costly signal is usually known as a romantic gesture.

Obviously, you cannot just throw cash at your date. That’s not a good romantic gesture, even though it’s definitely costly. And, dear non-economists, it’s important to understand that “cost” is not the same as “money”. Effort counts as cost, too. Sending a hundred customised text messages a day would easily qualify as a costly signal because the sender has to spend a significant amount of time and effort to produce these texts.

So, what is a good way to spend money or effort to create a romantic gesture? There are a two main things to consider, because there are two dangers you definitely want to avoid: you don’t want your gesture to come across as cheesy or creepy.

We’ve already discussed that you need a costly signal, so when we talk about avoiding cheesiness, this is not so much about how much a signal costs, but about how much thought you put into it. A signal that is too generic will not have the intended effect. If you just copy something you saw in some romcom, it will most likely appear cheap, even if it’s not. On the other hand, a very inexpensive gesture (in monetary terms) can be very romantic if you’re doing it right. When a friend of mine asked a girl out at the age of 14, he obviously couldn’t afford a candle-light dinner in a fancy restaurant. So he took her to a local branch of a well-known fast food chain, but he brought a table cloth, plates, cutlery, and, of course, the compulsory candle. A brilliant solution, and quite a creative one. However, even the most creative solution won’t help if you’re dating a completely humourless person (not sure why you would want to do that, but who knows). The most important point is to come up with something specific to the recipient. Roses: cheesy. Her favourite flowers that she casually mentioned in an earlier conversation: nice.

But while a romantic gesture won’t help you if it’s too cheap, too expensive isn’t a good idea either. If you do something completely inappropriate, your date will just assume something is wrong with you. A friend of mine met this guy in a bar who seemed to be quite nice. She agreed to go out with him the following Tuesday, but told him she might be late because she had to attend a business meeting in Hamburg. Upon hearing this, he offered to go to Hamburg on Tuesday, pick her up, and drive her back to the restaurant where they wanted to meet – in Cologne, which is about a four-hour drive. That was simply too much to do for someone you’ve chatted with for half an hour, and too much is creepy.

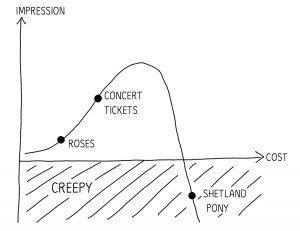

If we analyse the interrelation between cost and result, we will get what economists call an inverse U-shaped function, and it looks about like this:

Illustration 1: A pony is NOT a good thing to bring to a first date.

Tickets for your date’s favourite band: nice. Tickets for a sold out concert of his favourite band you spent three days driving across half the country to get: creepy. Unless he knows it’s your favourite band, too.

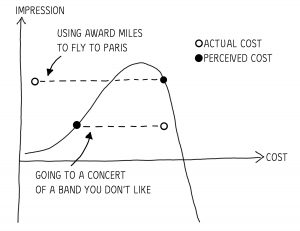

This difference is important because costs are subjective. Often, it’s impossible for your date to know how costly something is for you, so it’s all about their perception. I’ve been working as a business consultant for quite some time and have collected plenty of award miles, am very much used to travelling, and I just like being in different places. Having a date in a city other than my home town is a perk for me, not a cost (unless it is a very boring city). If I travel to Paris to see someone, the monetary costs of the plane ticket are negligible and the emotional costs of travelling are outweighed by the benefit of being in another place, which results in total costs close to zero. However, for most people the cost would probably be much higher, and so my date is likely to perceive the gesture as far more expensive than it actually was.

Illustration 2: Don’t go to a concert of a band you don’t like.

Without information, your date will use baseline figures to estimate your subjective costs, so take a moment to think about what the cost for an average person would be. Then, choose a gesture that is inexpensive for you, but will impress your date by just the right amount.

So what have we learned? A romantic gesture is an important measure to reduce uncertainty in the initial dating phase when you want to show someone you’re serious about them. A good romantic gesture is

- creative and specific to avoid being cheesy,

- not too expensive to avoid being creepy, and

- less expensive for you than it would be for the average person to avoid costs. This is written by an economist, after all.

And always keep in mind that uncertainty is two-sided, so even if you take all this helpful economic advise and come up with the perfect romantic gesture, you can never be sure what the result will be. You will reduce uncertainty for your counterpart, but not necessarily for you; and if you do get a reaction, you may find out they don’t share the same feelings. Or, as a non-economist put it in a less accurate, but far more romantic manner: A romantic gesture is an effort you spend that you cannot expect to get anything out of, in hopes of getting everything out of it.