Behavioral insights for public health

This case study illustrates how behavioral insights can help to design a fun campaign to improve public health. It builds on a real-world challenge, while the solution and the underlying data are illustrative examples only. [1]

Behavioral root causes: Have you ever stopped dieting?

If thoughts like ‘this ice cream won’t matter’ or ‘I will quit smoking tomorrow’ sound familiar to you, then you are in good company. Most people procrastinate once in a while, i.e. prefer things here and now as opposed to something more rewarding or healthier later. Procrastination is due to a present bias which is activated once we see an opportunity for immediate gratification. This behavior is part of our evolutionary legacy. In the past, we did not know when the next opportunity for food, rest, leisure, etc. would arise, so we had to take whatever we could get.

But times have changed. Today, 30 percent of the world’s population is either obese or overweight, factors that directly contribute to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer. This trend is hardly desirable from a public health and well-being perspective. So the question is what can we do about it? How can we stay closer to our long-term preferences when being confronted with instant temptations?

Behavioral design: Commitment, team spirit, and competition

In this case study, we illustrate how behavioral insights can inform the design of a public health campaign.

Behavioral science tells us that commitment devices are very successful means to overcome procrastination. A typical example is a person who deliberately commits herself financially to accomplish a certain task, for example, lose 10 kg by 1st of August next year. Accomplishment is later verified by an external referee, e.g. by weighing-in at the doctor’s office. If she fails to meet the goal, the money is transferred to a charity; otherwise, she gets her money back.

Financial commitments work quite well. Success rates range from 70% to 90% (please check out the fabulous page of www.stickk.com for more intriguing examples). The downside is that not all citizens suffering from overweight are actually willing or able to put themselves at a substantial financial risk. So relying on financial commitments will not solve the problem of procrastination at large.

The good news is, however, that commitment devices don’t necessarily need to include threats of financial harm to be effective. Social and/or psychological mechanisms might do the same job. Have you ever heard of the Spanish city of Narón? The city has launched an inspiring ‘community diet’ program, accompanied by a city-wide awareness campaign for a healthier lifestyle. 4,000 people have voluntarily signed up to this program and now jointly struggle to reduce a total of 100,000 kg over the course of two years.

The program is a great example of smart behavioral engineering. Instead of setting financial incentives, it refers to team spirit as main commitment device. Participants who contribute to achieving the group’s objective can expect to receive encouraging recognition from their fellow dieters; while, on the other hand, participants strongly deviating from the goal will be socially sanctioned.

Now imagine the city of Narón would compete in a ‘weight-loss challenge’ against another city, or, even better, against ten other Spanish cities in a nation-wide contest. In this scenario, not only team spirit would be triggered as social commitment device; there is another influential effect at play, competitiveness, which is likely to increase the willingness of a single participant to put even more efforts into a healthier life style – for the sake of her team’s success.

Behavioral campaign: A large-scale health contest

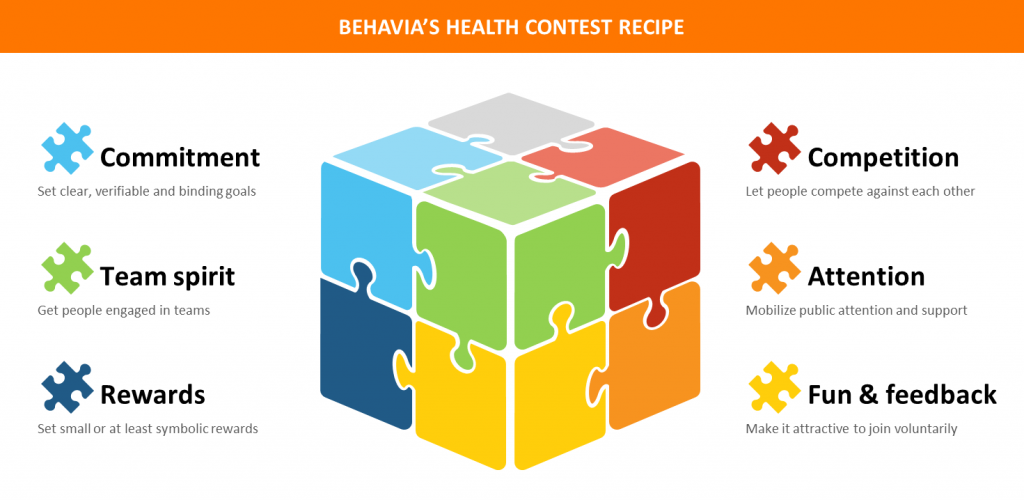

Commitment, team spirit, and competition are the basic ingredients of our large-scale health contest. The general idea is that various teams compete for the highest activity levels and weight loss. Let us see what other important items we could add to our weight loss recipe.

First, let’s think about adding public attention. National health authorities can accompany the entire program with awareness campaigns – just like in the case of Narón – and offer (at least) some symbolic trophies to the winning teams. Attention may not have a huge impact per se, but it creates a reinforcement effect for both team spirit and competition.

Second, let us revisit the finance front. Although we do not want people to put their money at risk, we can offer financial rewards to those teams which perform well during the contest. Rewards can be based on rankings, i.e. based on the comparison to other teams. Corporate partners could sponsor donations to the winning team’s charity of choice. Another option is to offer rewards based on milestones. For example, teams that achieve an important milestone such as weight reduction of 5%, can be rewarded with special discounts on healthy lifestyle products or insurances.

Third, people should have fun when participating! Cooperation with sports’ mobile applications would add gamification elements which underpin the contest-like framework and provide positive feedback through ‘likes’ as well as daily updates on the team’s sports activities, e.g. ‘your team burned 36,000 calories in the gym today’. In addition, it would be possible to compare the team’s performance to others, e.g. ‘the most active team burned 38,000 calories in the gym today. You folks are just 5 % behind’. This feature could further spur the ambition to compete.

Evaluation: How do people perform?

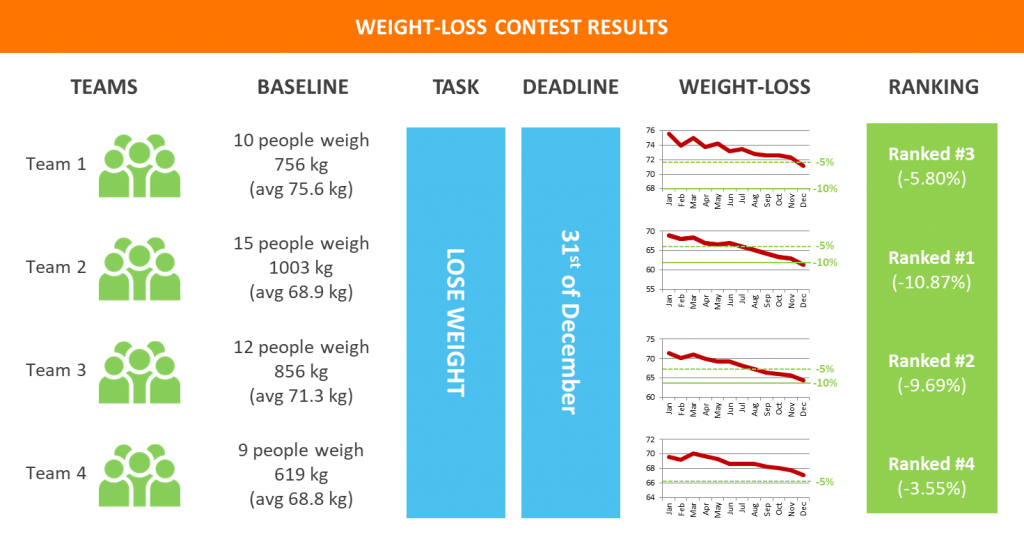

The impact evaluation is integral part of the health contest. In this example, we assume that all teams successfully lost some weight during the contest. The average weight losses range from 3.6% to 10.9%.

The teams could be ranked to determine the winners: the charities of the three winning teams would receive the sponsor’s donations. In addition, each team’s performance would be evaluated separately. If a team met a weight-loss milestone, its team members are rewarded with discounts on lifestyle products and services.

Key takeaway

The health campaign demonstrates how behavioral insights can help to empower people and promote a more active lifestyle. Its design is flexible and scalable to almost every environment and target group: whether at schools, firms, families, or neighborhoods – it can set the right incentives for people from all backgrounds and ages to join and get involved while having fun with others.

The design has informed the “Walk 30” campaign of the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia. Updates and progress reports are regularly published on the Ministry’s social media channels.

If you are also interested in creating your own heath campaign, please get in touch with us. We are always excited to learn more and help.

[1] Behavia makes no warranty, representation or undertaking whether expressed or implied, nor does it assume any legal liability, whether direct or indirect, or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information presented in the case study.