The perks of high self-control

Resisting temptation can be a real struggle. Self-control problems are life-long companions to many people who often find it hard to adopt better eating or exercise habits, or to stick to other plans they have set for themselves. In turn, the ability to exert self-control helps people achieve their long-term goals.

In this post, I discuss how economists and psychologists view self-control, how they measure it for research, and I summarize the main findings on the impact of self-control and my related experimental study.

How self-control is viewed across research disciplines

Self-control is a widely debated term in psychology, generally described as a mental ability, but also a cognitive process, affected by genetics and childhood experiences. In economics, the more common concepts are the related notions of present bias and inconsistent time preferences. These refer to the preference of a smaller reward now over a larger reward later, while when being asked about future trade-offs, a preference to wait for a larger reward. There are however also economists who investigate how self-control predicts life outcomes. They understand self-control as the ability to override undesired behavioral tendencies.

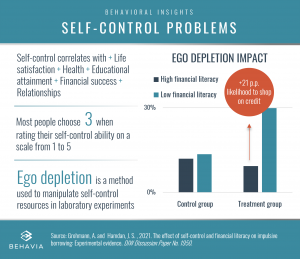

A standard procedure to measure self-control is using the Brief Self-Control Scale (SCS) developed by Tangney et al. (2004). Survey respondents are asked to read 13 statements that describe behavioral mechanisms related to self-control, for example “I am good at resisting temptations,” and rate how much these statements generally apply to them. The responses are measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates Completely disagree and 5 indicates Completely agree. Responses typically follow a normal distribution: many respondents choose 3, identifying with the statement to some extent, and fewer respondents agree or disagree completely with them.

An alternative to the SCS is using proxy variables relying on people’s real-life behavior that can be associated with low self-control, for example, being a smoker. Both the SCS and proxies are valid options to approximate the relationship between a person’s self-control ability and other variables.

Powerful predictor of all things good

There seem to be only perks of higher self-control. Studies link the trait to many desirable life outcomes, such as higher educational outcomes, success in the labor market, better health, greater financial well-being, stronger relationships, interpersonal skills, and overall life satisfaction (see, for example, Cobb-Clark et al., 2019). Self-control is also positively correlated with well-being on a within-person level. This means that respondents who report higher self-control than they did in an earlier survey on average also report increases in their well-being. This raises the interesting question of how stable a person’s self-control is. The answer is likely that there is certainly correlation over time, but some variation within people remains.

Can we manipulate self-control?

In psychology, there is a controversial discussion on why these within-person fluctuations in self-control form and how researchers could manipulate this process. Since the early 2000’s, some psychologists suggest that self-control is a state and finite resource, in addition to being a personality trait. When self-control resources are strained within a person, the energy available to the self is low and the capacity to control the mind over habituated responses is impaired. This is thought to be the result of so-called ego depletion. As a consequence, the ability to exert further self-control decreases in the short term. To make this theory tangible, imagine if you resisted unhealthy food all day, but in the evening do not manage anymore to say “No” to some sweets.

The ego depletion theory has been the subject of countless controlled experiments around the world. So-called ego depletion methods rely on strenuous unrewarding exercises, demanding constant suppression of a habituated behavior. They cause mental fatigue and lead the participants to a state of depletion, assumingly reducing their ability to exert self-control in subsequent tasks. At the same time, control participants perform exercises which are not considered depleting. A classic ego depletion method is the ‘letter-crossing task’ where, first, a habit is instilled among participants who must cross out a certain letter from a given text for a short while. Then, only the treated participants are asked to follow a more complex rule: crossing out the letter if a vowel does not follow or precede the letter in a certain way. This experimental design aims to cause depletion among the treated by asking them to override their habit. This procedure is assumed to allow researchers to measure the causal impact of lowered self-control on decision-making observed in the experiment.

Experimental evidence on ego depletion and impulsive shopping

Relatedly, our experimental study investigates the impact of self-control on impulsive debt-taking for consumption. From a survey representative for households in Germany, we first showed that self-control correlated with a lower probability to get into repayment difficulties with consumer debt. Motivated by this observation, we aimed to causally investigate the relationship between low self-control and impulsive shopping on credit. We implemented a lab experiment and used the ‘letter-crossing task’ to produce exogenous variation in the self-control ability between the otherwise comparable treatment and control groups.

We found that the ego depletion treatment reduced the participant’s ability to concentrate significantly. When constructing an index from several manipulation checks, we showed that the treated were indeed, on average, significantly more depleted. Our main result was that the treated were about 7 percentage points more likely to shop on credit and spent, on average, 53 percent more money in our experimental setting compared to the control group. While these differences were in the expected direction and suggested that ego depletion increased the probability to impulsively borrow for consumption, they were not statistically significant on the common levels. However, we identified a sub-group of participants who reacted strongly to the treatment. Treated participants with low financial literacy were 21 percentage points more likely to shop on expensive credit compared to the treated with high financial literacy. This suggested that self-control problems could be compensated for with financial literacy.

So far, few experimental studies in behavioral economics focus explicitly on self-control problems. Ego depletion remains a method predominantly applied and discussed in psychology research. However, continued efforts to test and develop ways to influence self-control in experimental research can lay the basis to better understand the causal impact of the powerful ability.

Interestingly, recent research questions the ego depletion process and believes ego depletion only exists for those who believe in limited self-control resources: the theory may be a self-fulfilling prophesy. Further research in this direction could be helpful, for example to assess the impact of information treatments on ego depletion.

References

Cobb-Clark, D. A., Dahmann, S. C., Kamhöfer, D. A. & Schildberg-Hörisch, H. (2022). The predictive power of self-control for life outcomes. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 197: 725-744.

Grohmann, A. & Hamdan, J. S. (2021). The effect of self-control and financial literacy on impulsive borrowing: Experimental evidence. DIW Discussion Paper No. 1950.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F. & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2): 271-324.

Dr. Jana Hamdan

Jana Hamdan is a Senior Researcher at Behavia and a Post-doctoral researcher at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). She holds PhD in Economics and has conducted experimental and survey-based research in various countries. Jana has published policy and academic articles, for example in the peer-reviewed Journal of Development Studies.