Why would we pay someone to punish (or tax) us?

Imagine your livelihood and that of your neighbors depends on a common resource that replenishes itself naturally. As a community, you learned over time, with a high degree of certainty, the replenishment cycle and were able through social norms and customs to share the common resource. Recently, however, the replenishment cycle rapidly became unpredictable and you, as everyone else, became uncertain about your share. To ensure that you have enough you rush to get your share of the resource and thus putting your neighbors in a difficult position: to avoid losing their share, your neighbors preemptively try to get their share faster than you and as a result the resource gets depleted even faster. This is a classic example of the “tragedy of the commons” wherein self-interests override the interest of the group. So, what can you do to handle the situation? One way of managing the resource is to create an institution that manages the access. But how exactly should this institution be designed? And who would pay for it?

The struggle of Cambodian farmers

Together with Andries Richter (Wageningen University) and Tum Nhim (UNDP Cambodia) we conducted an experiment in Cambodia to analyze what kind of institutional design would be appropriate to handle these social dilemma situations. Why Cambodia you ask? The problems of Cambodian farmers can be seen as exemplary for many regions in the Global South. Traditionally, Cambodian farmers rely on the rainy season to replenish lakes and rivers to provide sufficient water for water-intensive crops such as rice. Yet, climate change has disrupted the rainfall pattern: the rainy seasons became unreliable in terms of timing, duration, and amount. As a result, water became a commodity whose degree of scarcity varies somewhat unpredictably over time.

With less water available the risk of severe water scarcity increases for all farmers. The degree of individual water scarcity depends not only on rainfall patterns and the quantity available but also on the geographical proximity towards water sources such as rivers and lakes. As a result, one often finds that people nearer to the water sources try to ensure sufficient water for their own fields, thereby leaving others further away without water.

While water in Cambodia was traditionally managed through informal institutions such as social norms, these are not sufficient anymore. Informal institutions are deeply embedded in the social-ecological system they help to govern. These long-standing rules are challenged by the disruptive effect of climate change impacts. Given enough time, communities might be able to establish new informal rules but given the precarity of the livelihood of rice farmers, this might be too slow. Hence, to increase security in water access, some communities/villages have started to use more formal institutions called “Farmer Water User Communities (FWUCs)”. The arrangement is that the members pay an irrigation service fee and in turn this organization is responsible for keeping the irrigation infrastructure in good quality, ensuring provision of irrigation to their members, and enforcing the written rules. These FWUCs vary greatly in their effectiveness depending on the exact institutional design and the community. Thus, it is important to test what design works best for each community and not assume a one-size-fits-all solution.

Experimental Design

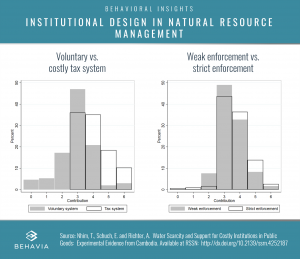

We designed experiments that mimic the basic setting that these Cambodian farmers are exposed to. There is a resource that is shared by a community that needs investments to ensure that the resource can be used (such as maintenance of irrigation infrastructure). The investments towards this public good will provide equal benefits to everyone in the community independent of how much each person contributed. To manage the investment, they can vote which rules apply (the institutional design). We have two settings. In the first one they choose between a voluntary contribution system (everybody contributes as they see fit) or a tax system (everyone is forced to contribute a minimum). The voluntary contribution system is free of charge whilst the tax system comes with a service fee. The second institutional choice is between a system that states a minimum contribution level and punishes people that undercut the amount, but the enforcement system is ineffective (only about half of the offenders get caught), or they can opt for a system that has an effective enforcement (every offender gets caught) but again, this institutional design can only be maintained with a fee.

Results

We find vast support for the costly institutions with about 62% choosing the institution that comes with a fee over the free one. Preferences between costly institutions differ but only 23% choose both institutions that were free of charge. The strongest support for functioning fee-based institutions comes from people that experienced water scarcity in the past. The people least likely to vote for a tax system are farmers who own land very close to the water source, indicating that they feel confident to access enough water independent of the institutional design.

Comparing the two fee-based institutions we find that the tax system provides a higher welfare than the effective enforcement system which is mainly driven by the higher contributions towards the public good in the tax system. The tax system provides the highest welfare of all four institutional settings even though the mandatory fee means that the voluntary contribution system as well as the ineffective enforcement can reach welfare levels that are not possible in the tax system while the costly punishment system produces the lowest welfare of all four systems. The high welfare in the tax system stems from the strong crowding-in effect (figure 1) which is probably driven by people’s desire to make an active positive contribution on top of the mandatory tax contribution.

Overall, we see that people are willing to pay for functioning formal institutions that are able to punish offenders reliably since this reduces individual uncertainty in water access. We found that Cambodian farmers value institutions that ensure equal benefits and equal contributions. When designing formal institutions, it is paramount to consider local norms and cultural aspects to gain acceptance. Cambodian society is very community oriented with strong preferences for equality and fairness. Thus, any formal institution that appeals to these values whilst ensuring a successful natural resource management will more likely be accepted.

References

The working paper can be found here: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4252187

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons: the population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. science, 162(3859), 1243-1248.

Dr. Esther Schuch

Dr. Esther Schuch

Esther Schuch is a Senior Researcher at Behavia and an Affiliate at the Research Institute for Sustainability (RIFS) – Helmholtz Centre Potsdam. She holds a PhD in Environmental and Behavioural Economics and has conducted experimental and survey-based research in various countries. Esther has published policy briefs and academic articles addressing topics such as cognitive biases, decision-making, and social norms.