Forecasting the duration of emotions

A motivational account and self-other differences

Have you ever day-dreamed about winning the lottery? You can almost see yourself being happy until the end of your days, spending great holidays in paradisiac beaches while at the same time investing your money wisely to prosper. And what about if you got dismissed from your job for professional misconduct? You would not have time to feel sad or concerned – you’d apply to two or three amazing positions and would certainly get two (or even three!) offers.

It is common to think about the future and to make predictions about how certain events will affect us. Some of these predictions help us to make decisions, such as whether we should buy a lottery ticket today or try to meet our job deadlines more often! The only problem is that every time we forecast feelings associated with great or terrible events, we tend to over- or underestimate them and their consequences.

This is a result of our wishes and desires! Wishing for the excitement of positive events and ignoring the burden of negative ones is a strategy used to maximize our well-being and to avoid preparing ourselves for painful moments. In 2018, I was part of a research team that investigated this assumption by gathering information from hundreds of people on how they estimated the impact of desirable and undesirable events, imagining as if these were to happen to themselves or to others. We predicted that excitement of positive events would be overestimated when compared to grief of negative events. Since we see ourselves as better-than-average, we also predicted that this asymmetry would not be true when people made predictions about how others would feel.

In one of the experiments we conducted, some participants were randomly exposed to a series of hypothetical positive (e.g., having their work recognized with an international award; graduating in the top three of the class; winning the lottery) and negative events (e.g., being betrayed by a significant other; having cancer; getting fired) as if they were happening to themselves. Other participants were exposed to the same hypothetical events as if they were to happen to someone else. After each positive/negative event everyone was asked to estimate for how long they (vs. someone else) would feel happy/sad and whether each event was desirable.

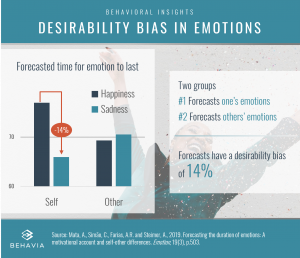

Individuals estimated their own happiness associated to positive events to extend for a longer period than their sadness associated to negative events. What about others? Others lived for a similar period both their happy and sad feelings. But it is not new that what is positive is more desirable. We also confirmed that association between positivity and desirability. To disentangle positivity from desirability, in one of the other experiments, some participants were randomly exposed to scenarios where both desirable and undesirable events were inducive of either negative or positive feelings as if they were happening to the self. Other participants were randomly exposed to the same event as if they were happening to someone else. After each event, everyone was asked to estimate for how long they would feel e.g., grateful/angry. Regardless of their valence, feelings associated with desirable events are estimated to last longer than those associated with undesirable ones. Once again, this asymmetry between desirable and undesirable events was not true for other people.

Motivated thinking, or our tendency to accept more easily what we want to believe in, is a powerful tool that influences decision-making by maximizing the experience of desirable affective states. However, we believe that desirable asymmetric forecasts for the self may have harsh consequences on different grounds. Particularly, in risk-taking behavior: If we believe that our own desirable feelings are supposed to last longer than our undesirable ones, we might underestimate the consequences of our undesirable behaviors, becoming more vulnerable to irrational financial decisions or unhealthy behaviors.

Reference: Mata, A., Simão, C., Farias, A. R., & Steimer, A. (2018). Forecasting the Duration of Emotions: A Motivational Account and Self-Other Differences. Emotion.

Dr. Cláudia Simão

Cláudia Simão is a Senior Researcher at Behavia and an Adjunct Professor at Católica-Lisbon School of Business and Economics. She has a PhD in Experimental Social Psychology, and over the last 10+ years she has designed 500+ research studies/experiments on human behavior. Cláudia published 35+ scientific articles in top journals addressing topics such as prosocial behavior, decision-making or positive emotions.