Can customer journey mapping help in designing behavioral experiments?

Customer journey mapping is a widely used tool for both commercial and non-commercial sectors to help organizations optimize processes, generate insights, and eventually improve the customer experience. In a nutshell, the exercise involves breaking down the customer journey into stages, each stage detailing the points of interaction between the organization and the customer. At each of these points, we list the actions and emotions of the customer, the process owners/stakeholders, challenges, and opportunities, among other things.

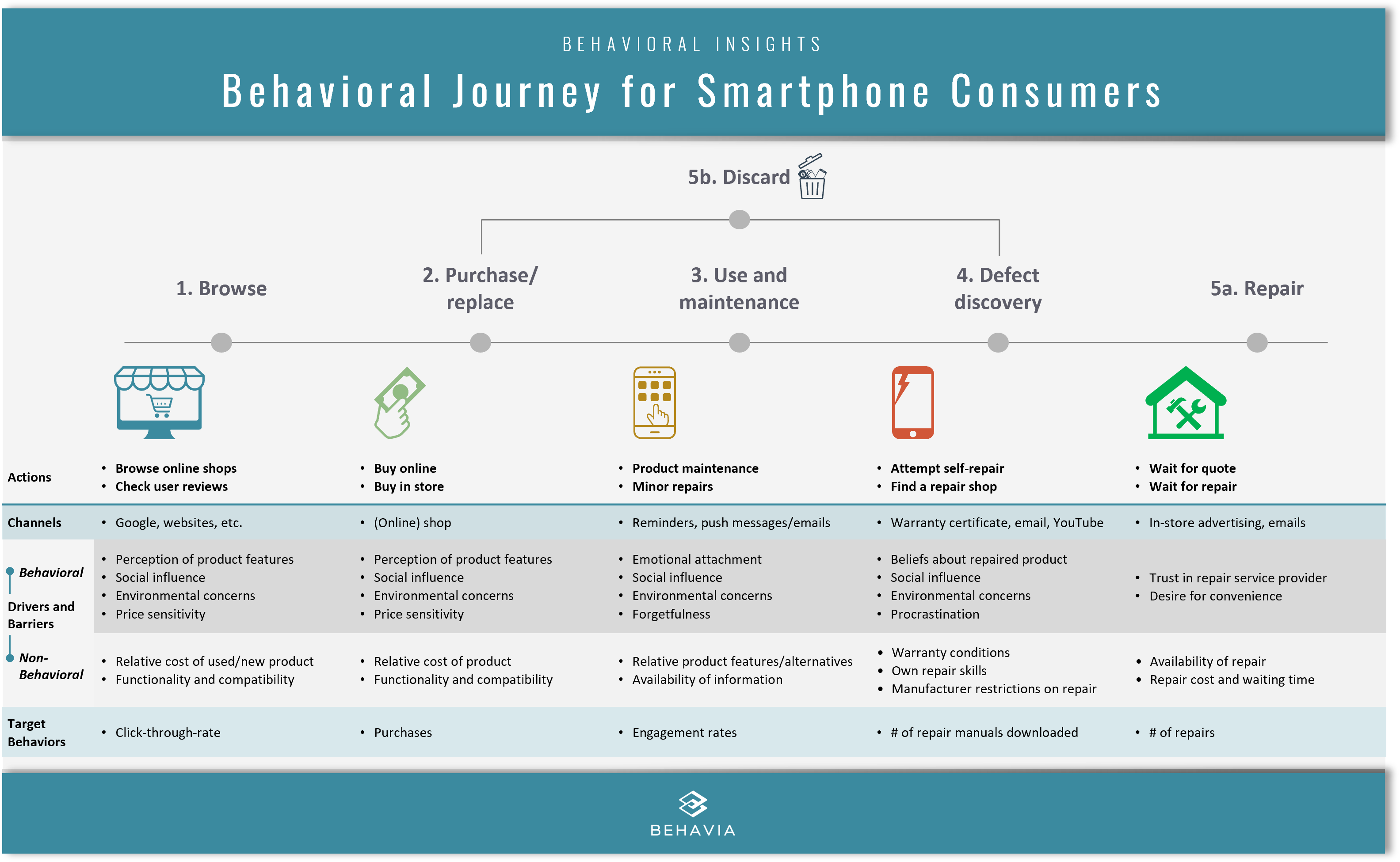

While beneficial to understanding your target group’s behavior, a typical CX-focused journey falls short of what is needed for evidence-based behavioral experiments. But, since behavioral change is all about the context, you can use CX journeys as starting points and expand them by fleshing out important factors in the decision-making context. Additionally, grounding yourself in your target group’s perspective, using journeys helps reduce biases or prejudices you may have brought with you. And if not for these reasons alone, mapping the entire journey in stages with proper measures makes it easier to spot and avoid undesired side effects that could be carried from one stage to another. In other words, your treatments should be less likely to backfire when you know the entire story.

The nuts and bolts of a behavioral journey

The linchpin of any behavioral intervention is to know the drivers behind the undesired behavior (or the barriers to the desired behavior). To borrow from Nietzsche, those who have the “why” of behavior can know the “how” of change. Applying this to behavioral journey mapping, the primary focus is on both behavioral and non-behavioral drivers to help structure and narrow down the ‘why’ question by stage.

Another indispensable part of any behavioral experiment is the target behavior: what is the desired behavior? Distinct from actions (e.g., looking at an ad) or goals (e.g., improve KPIs), target behaviors are measurable behaviors that a person must do to move from stage 1 to 2. For example, clicking a link to proceed to the registration page after seeing an ad or pressing ‘1’ after a customer service call has ended to participate in an evaluation survey (of course, you might also use self-reported behavioral intentions or similar proxy behaviors if you are conducting survey experiments). By the same logic, a behavioral barrier is what stands in the way and a behavioral driver is what makes it easy for a person to progress from one stage to another. From a process perspective, our task then becomes figuring out the optimal behavioral flow that reduces the friction between intentions and desired behaviors and stimulates progression through the journey – assuming at least a moderate interest in what is being offered by the organization.

It must be noted here that behavioral barriers are the factors related to a person’s cognition, perception, psychosocial context, and information or decision-making processes and abilities. Non-behavioral barriers, on the other hand, would be issues related to the incentive structures, such as the financial rewards system for employees, or problems related to the infrastructural context, such as those that impact a person’s mobility. Such problems are not suitable for behavioral experiments since the underlying problems are not behavioral in nature.

A quick 3-step not-set-in-stone guide to behavioral journey mapping

The following steps are not exhaustive but following them can surely make your customer journey map more behavioral.

1. Stage mapping – walk a mile in their shoes

Consciously go through the real-world experience of the journey you are trying to improve. Note down the journey’s progression points, i.e., the key points where you move from one stage to another. The progression points will determine the number of stages you have. If you cannot go through the journey yourself, interviews and focus groups with target audience and stakeholders are good alternatives.

2. Drill down each stage – use the power of sympathetic introspection

At each stage, you will need to identify the typical actions, the intervention channels, and what possible behavioral or non-behavioral drivers/barriers could motivate or prevent you from proceeding from one stage to the next. You can do so by asking these three questions:

i) What can you do at each stage (actions)?

ii) How are you doing it (channels used)?

iii) Why are you doing or not doing it (behavioral and non-behavioral drivers/barriers)?

A golden rule for the perplexed: if a ‘why’ is beyond the person’s direct control, it’s most likely a non-behavioral driver.

3. Determine the target behavior for each stage

Ask the following questions to identify the target behaviors:

i) What do you need to do to at this stage of the journey to progress to the next?

ii) How do you observe this behavior through the available intervention channels in this stage?

Another golden rule: if it’s not measurable, it’s most probably not a suitable target behavior.

It is important to bear in mind that behavioral journey maps alone are not sufficient to draw firm conclusions about the underlying root causes of behaviors. Even if backed by literature, the behavioral drivers and barriers should be treated as educated assumptions or hypotheses. Behavioral experiments in real-world context are the only way to test your hypotheses and turn your assumptions into evidence-backed statements.

Mohamed Hassan

Mohamed Hassan is a Senior Consultant for Behavioral Public Policy at Behavia. He holds a Master in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from the University of Witten/Herdecke, Germany, and has more than 10 years experience in the GCC. He is specialized on copywriting, online experiments, qualitative analysis, research scoping, and hypotheses development. Besides his work at Behavia, Mohamed is a screenwriter and active member of FMMN movie makers collective in Berlin, Germany.