Reflections on the future of Behavioral Public Policy

Over the last couple of months, we attended several conferences in Behavioral Public Policy including the IAREP in Tartu, BX2025 in Abu Dhabi, and this week the IBPPC in London.

Each of these events was inspiring and we enjoyed learning from our peers and colleagues about the latest advances in our field. At the same time, we sometimes found ourselves a bit surprised by the direction in which discussions are heading. In particular, our perspective on the future of BPP seems to differ in several ways from the topics currently dominating the conversations.

So, we wrote up our thoughts – beginning with our understanding of BPP’s core value proposition, moving to ideas for new types of interventions, and concluding with suggestions for new frontiers that we believe are worth exploring.

Our intention is not to provide ultimate answers, but to offer different perspectives that we hope will spark discussions or, at least, encourage debates.

I. BPP’s value proposition

Despite the global rise of BPP over the last 15 years, our approaches are still not fully integrated into most policy cycles. Why is that? We think it is worth taking a step back and asking what exactly does BPP have to offer to policymaking and policymakers. We think that, at its core, our field rests on two principles:

- Human-centered policy design: we examine policy through a behavioral lens, trying to make policy designs more effective and predictions about behavior more accurate.

- Evidence-based insights: we rigorously evaluate policies and isolate their causal impact by controlling for other possible influences.

In our view, if BPP is to secure a permanent seat at the policymaking table, we need to prove – and keep proving – that these two principles create real added value to policymakers. At present, however, we think the balance is off. Policymakers associate the human-centered pillar with nudges, and evidence-based insights with results from one-off experiments.

Don’t get us wrong: nudges and one-off experiments have played an important role in placing behavioral insights on the policy agenda. Yet, as the field matures, they risk confining us to a small part of our toolbox. We think it is time to go beyond that.

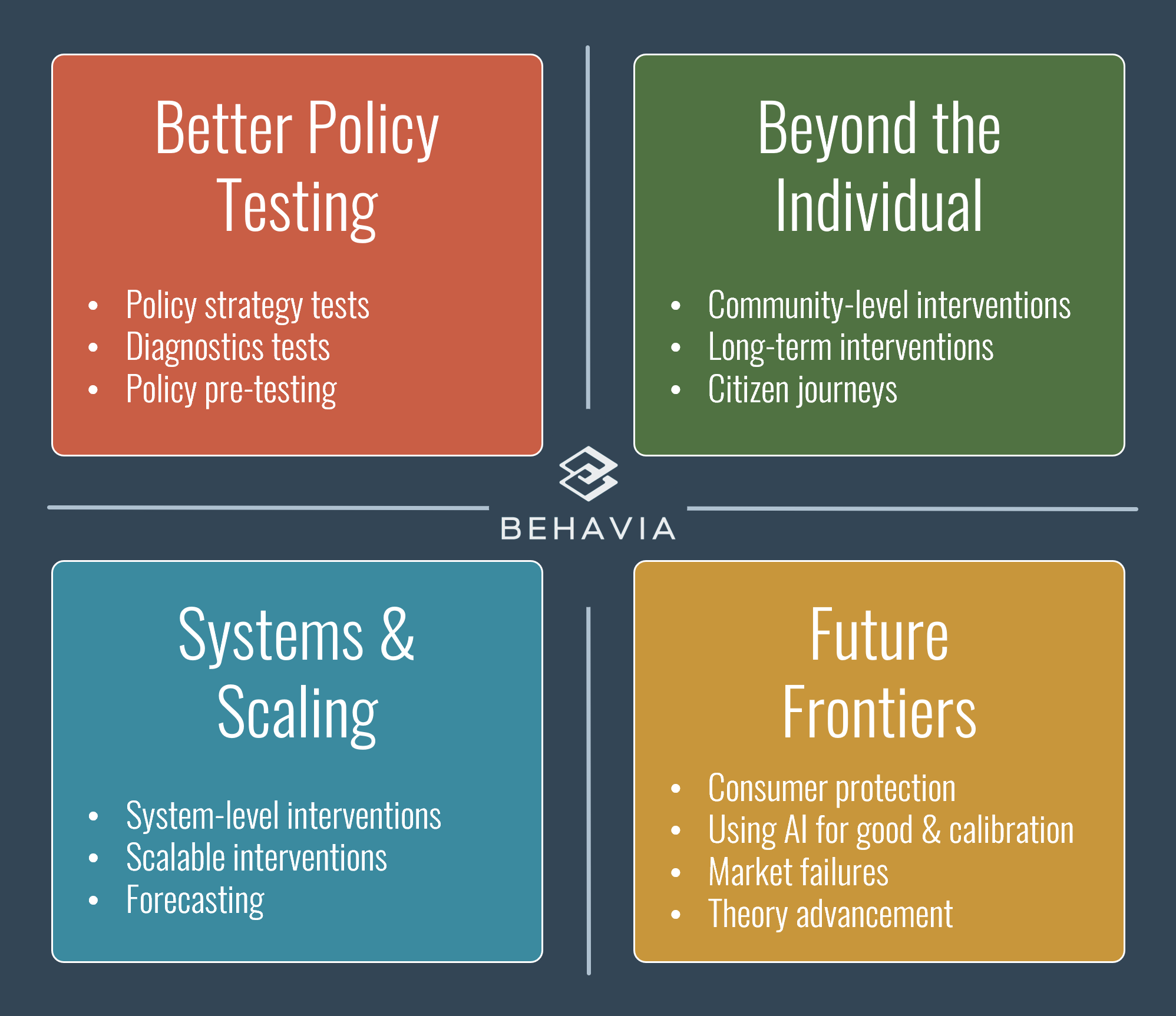

II. Behavioral Public Policy 2.0

We suggest developing new interventions along three major themes.

1. Better policy testing

- Policy strategy tests: let us show policymakers that they can use BPP for strategy testing. For instance, which strategies – awareness campaigns, education, incentives, nudges, or boosts – are most effective for a given policy problem? Are incentives more effective than nudges in reducing smoking prevalence among adolescents? Are bundles better than single strategies? What happens if we repeatedly expose people to strategies over a period of time? These are inherently behavioral questions and we have the methods to provide empirical answers.

- Diagnostics tests: we agree that better diagnostics should be promoted as the foundation of sound policy design. But to convince policymakers, we should also deliver proof that diagnostics improve outcomes. One approach could be solution contests in which different teams develop policy responses to the same complex problem, under identical conditions but using different diagnostic tools. One team applies the standard approach, another qualitative assessments, and a third a system-level analysis. Their solutions could then “compete”, for instance, in a survey experiment to see which one resonates most strongly with participants.

- Policy pre-testing: let’s stay for a moment with survey-based experiments. They are ideally suited for policy pre-testing: relatively cheap, hypothetical, and, thus, risk-free. This allows us to test legal regimes as a whole – not just incremental changes to policy parameters. In tax compliance experiments, for example, participants could be assigned to different “worlds” – ranging from the complicated status quo in a country to simplified flat tax regimes – and tasked with filing taxes under conditions that allow cheating. Measuring correct declarations and overall tax revenues across conditions gives policymakers early evidence in domains often dominated by ideology and anecdotal evidence.

2. Beyond the individual

- Community-level interventions: let us take inspiration from development economics and focus more often on communities as units of intervention. This would allow us to measure aggregate effects that incorporate group dynamics and cultural context – moving beyond individual choice. For example, an energy-saving nudge might be more powerful in reducing household energy consumption, while a community activity, e.g., picking up litter in the neighborhood, might also produce positive spillovers such as reduced water use and stronger community belonging.

- Long-term interventions: quick pilots are useful but often insufficient to capture complex decision-making over time. We believe it is time to do deeper and longer interventions that address complex behaviors – even at risk of finding null effects at first. In education, for example, we should try to identify the most effective curriculum components and sequences for improving learning outcomes. In labor markets, we should test different combinations of financial support, penalties, counselling, and training to learn what works best in activating job seekers. In health or financial literacy, we could examine how to support habit formation and long-term planning among young adults.

- Citizen journeys: BPP has often been confined to single policy compartments, i.e., specific areas under the jurisdiction of a given government entity. We believe we should advocate for pursuing an overarching approach that optimizes entire citizen journeys. For instance, if the goal is to have more highly qualified musicians, is it better to invest in early childhood music education, advanced university programs, employment subsidies, or intellectual property protection? Only trials across life and career stages can answer this empirically.

3. Systems, scaling, and forecasting

- System-level interventions: system-level analysis is essential to identify structural impediments and interdependencies. Yet, we believe qualitative mapping alone is not enough if we want to remain evidence-driven. Where nationwide RCTs are infeasible, we should learn from public economics and related fields, using quasi-experimental designs and advanced statistical models to infer or, at least, approximate causal effects.

- Scalable interventions: the issue of scalability is already high on the BPP agenda. We need to answer not only whether something works, but whether it is worth adopting at scale. How can we do this? In practice, by tracking all costs incurred during development, implementation, enforcement, etc. and comparing them against impact. The resulting measure of social return on investment (S-ROI) will show policymakers how many units of behavioral change can be generated with a given budget. With limited resources, such comparisons would likely guide decision-makers toward scaling the most efficient solutions.

- Forecasting: progress in system-level analysis and scalability should also allow us to improve our forecasting. In time, we should be able to predict with confidence how a tax reform would affect tax revenues, social cohesion, and public opinion. Or, with respect to public health, how to allocate a fixed health budget most effectively across healthy lifestyle promotion, risk prevention, and treatment.

III. Future frontiers for BPP

Yet, there is much more to do than “just” designing new interventions. We believe we should also support the advancement of our societies as a whole.

- Consumer protection: as consumers, we all face increasing risks from dark patterns, including hyper-personalization, misinformation including fake news, fake pictures and videos, and other manipulative practices. BPP should play a stronger role in empowering consumers’ agency to become more resilient decision-makers, especially among groups who are systematically disadvantaged. For example, adolescents need better protection from manipulative buy-now-pay-later schemes, while senior citizens should be safeguarded against contractual lock-ins and intentional sludge.

- Using AI for good: while AI’s risks are widely debated, we think its potential for consumer protection remains underexplored. Imagine companions that support seniors troubleshoot their mobile phones, monitor medication intake, point households to supermarket discounts, or help us filling our taxes in 15 minutes. These are just some application areas in which AI could soon be deployed to enhance consumer wellbeing. In this regard, BPP must ensure that policies and regulations for AI are human-centered, guiding innovation toward inclusive growth and societal resilience.

- AI calibration: current AI forecasting tools still underperform relative to expert judgment. Even CENTAUR* only barely outperformed our classic social utility models that were never designed for point predictions. Perhaps the path to better AI models is not more data, but better data. Can we design behavioral experiments that provide the data AI needs for better calibration? We think this should be explored.

- Addressing market failures: many of today’s pressing challenges are collective action problems. Yet, despite the advancement of academic research in these areas, applied BPP has often shied away from these wicked problems. How can individuals be encouraged to contribute more to public goods – locally, nationally, and globally? How can people be made more aware of the negative externalities of their actions – such as pollution, child labor, or animal suffering? Can we design mechanisms to counteract diffusion of responsibility? It is time to start translating academic research in these areas into practice.

- Theory development: finally, we should invest more effort in building domain-specific theoretical models that draw on existing research. Education interventions should be grounded in learning theory and child development research; financial wellbeing initiatives in theories of risk and uncertainty; health interventions in models of habit formation or risk perception. We, as practitioners, can – and should – do better than relying on generic models across domains and at least share challenges with our academic peers to help advance behavioral decision theory.

We hope our thoughts are of interest, that they spark some new ideas, or, at least, provoke debates. Most importantly, we look forward to hearing your perspectives – whether in agreement or disagreement – and to continuing this collective effort to make Behavioral Public Policy not only relevant, but indispensable for designing smarter, fairer, and more resilient policy systems.

Manuel Schubert and Joana Reis, September 2025

*Binz, M., Akata, E., Bethge, M., Brändle, F., Callaway, F., Coda-Forno, J., … & Schulz, E. (2024). Centaur: a foundation model of human cognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.20268.